Galaxy users, take note: Samsung’s probably selling your data

news analysis

Jan 22, 20209 mins

AndroidMobileSamsung Electronics

When you buy a Galaxy phone, Google's promise to protect your information isn't the only one that applies.

Relying on Google services, as most of us Android-carrying primates do, comes with a certain tradeoff. It’s no big secret or anything: Google makes its money by selling ads, which are more effective when they’re catered to our interests — the subjects we tend to search about, the things we buy ( when Google knows about ’em, at least), and often even the places we go with our location-enabled phones in tow (and/or in toe, for the monkeys among us).

That’s all par for the course, as I frequently say — part of the deal we all accept when we use Google services. That’s what makes it possible for Google to give us top-notch apps for free, and it’s also what opens the door to certain advanced features that wouldn’t be possible without that information’s presence.

What you might not realize, though, is that if you’re using an Android phone whose manufacturer makes significant modifications to the operating system or the system-level apps around it — any phone other than a Google-made Pixel or a Google-associated Android One device, really — there’s a decent chance the creator of your phone is adding its own layer of complexity into that arrangement. And even though Google itself doesn’t ever share your data with anyone, the company that creates your phone might be using its position to double-dip and directly profit off the same personal info you assume is protected.

That certainly seems to be the case with Samsung. In addition to making a hefty chunk of change from selling you hardware, Samsung appears to have quietly created an intricate system for collecting different types of data from people who own its phones and then generating extra revenue by selling that data to third parties — or sometimes using the data to power its own self-run ad network. That has the potential to be disconcerting for anyone and particularly red-flag-raising for businesses and enterprises, where information protection is an especially pressing priority.

For all the times I’ve complained about the complexity and confusion created by Samsung’s insistence on gunking up Galaxy phones with redundant versions of Google services, it never occurred to me that part of the reason it was doing that was to dip into user data and turn it into a secondary stream of income. It wasn’t until the crew from XDA Developers noticed a newly present setting in the Samsung Pay app the other day, in fact, that such a notion crossed my mind.

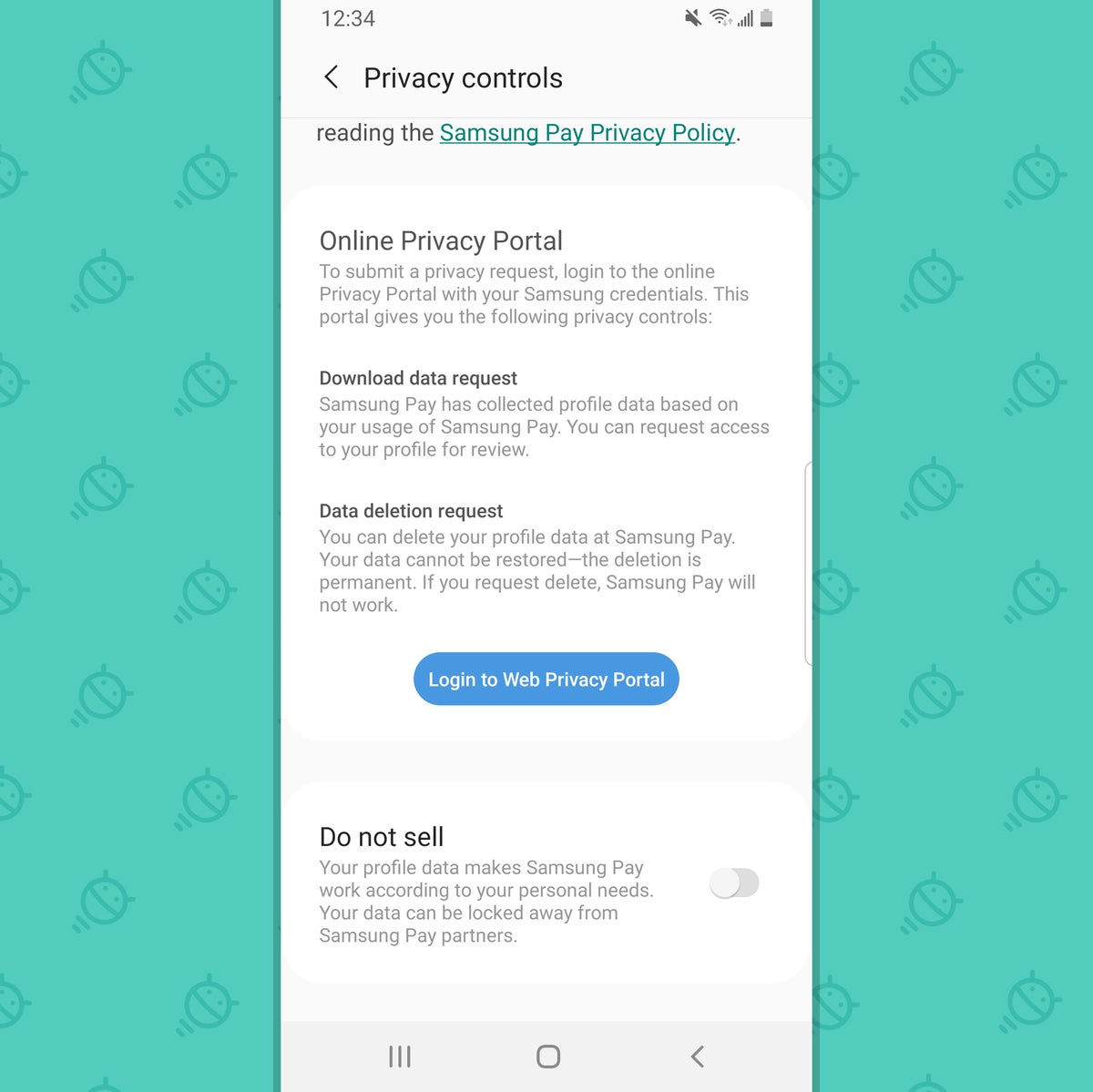

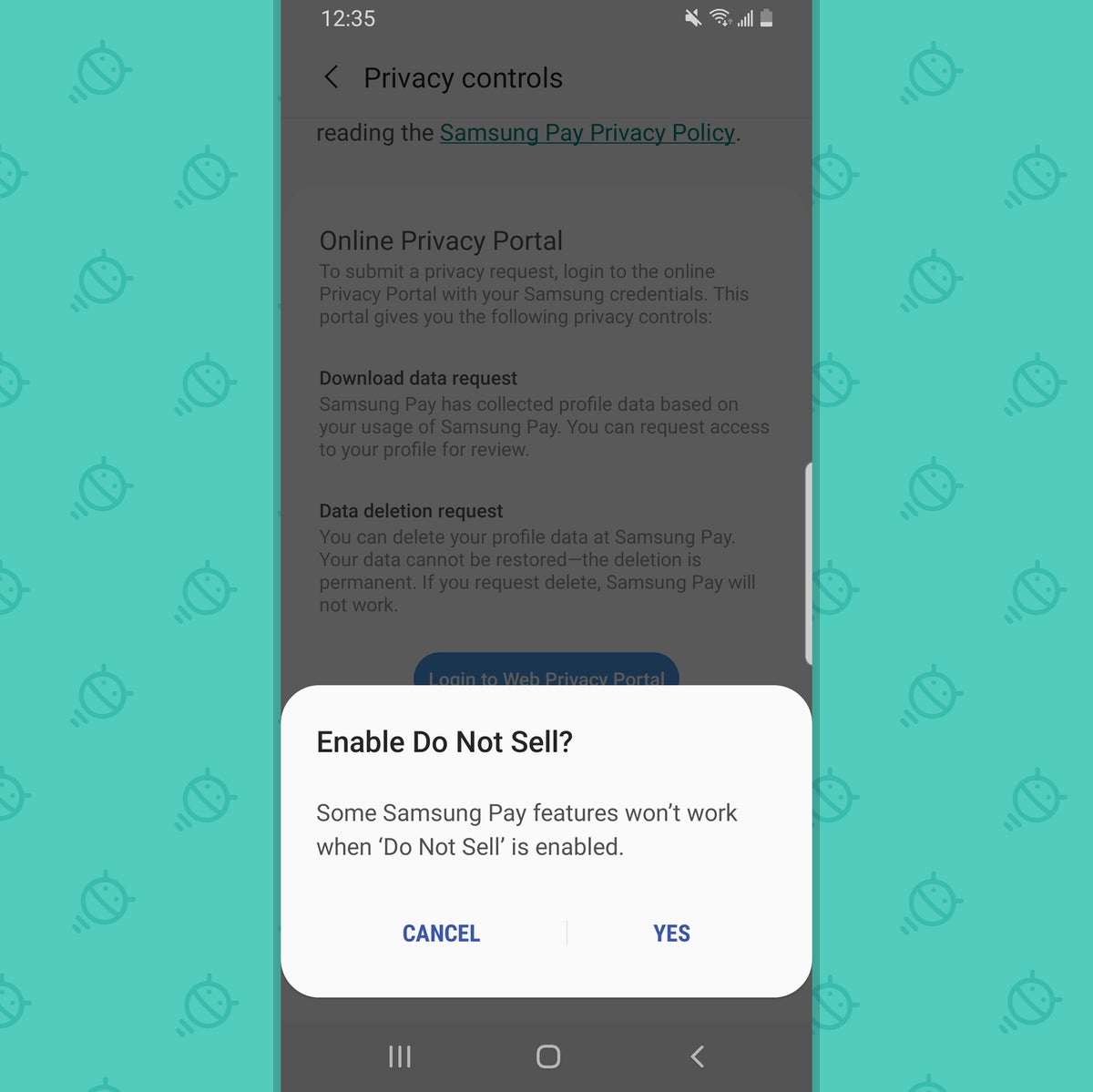

Samsung, as XDA discovered, recently added a toggle into its Pay app’s settings called “Do not sell.” If you find it and activate it — and no, it isn’t activated by default — then and only then, your payment-related data “can be locked away from Samsung Pay partners.”

JR

JR

Samsung does warn you that some of its Pay features won’t work if you flip that switch, though it isn’t immediately clear which specific elements of the app it’s referring to.

JR

JR

This switch’s addition seems to be tied to a new set of privacy regulations enacted by the state of California: the California Consumer Privacy Act, or CCPA, which went into effect at the start of this year — on the same day that Samsung’s privacy policy was updated. It’s not clear if the same Samsung Pay “Do Not Sell” option is being provided to Galaxy device owners outside of the U.S., but what is clear is that Samsung didn’t seem to provide this option to anyone — or make it at all clear that it was apparently selling payment-related data to third parties — before this point.

And digging deeper into the company’s privacy policy, it seems this isn’t the only place where such data dipping practices are being employed. As part of the policy’s “California Consumer Privacy Statement” — again, making the disclosure specifically to California residents, as now required by law — Samsung says:

We may allow certain third parties (such as advertising partners) to collect your personal information. You have the right to opt out of this disclosure of your information.

It also warns California-dwellers that prior to the CCPA’s passage, it “may have” sold several specific categories of alarming-to-the-IT-department info, including:

Identifiers such as a unique personal identifier (such as a device identifier; cookies, beacons, pixel tags, mobile ad identifiers and similar technology; other forms of persistent or probabilistic identifiers), online identifier, and internet protocol address

Commercial information, including records of products or services purchased, obtained, or considered, and other purchasing or consuming histories or tendencies

Internet and other electronic network activity information, including, but not limited to, browsing history, search history, and information regarding your interaction with websites, applications, or advertisements

Inferences drawn from any of the information identified above to create a profile about you reflecting your preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities, and aptitudes.

Yikes. And that’s barely scratching the surface. The company notes that it also may have “disclosed” even more personal info to “vendors” for “a business purpose” — everything from your name, address, and phone number to your signature, bank account number, credit card number, purchase history, browsing history, search history, geolocation data, and once again that lovely-sounding collection of “inferences drawn” from all that info.

I wish it ended there, but the more you dig, the more unsettling stuff you uncover. The privacy page for Samsung’s Customization Service — something that’s integrated all throughout Galaxy devices’ software and the Samsung-branded apps associated with it — collects much of the same device-specific sorts of information. It taps into data about what apps you use on your device along with what music you play on the phone, what websites you visit, what searches you make, and where and when you’re taking pictures. It also relies on Samsung-made apps like the company’s custom Calendar and Internet (browser) utilities to analyze your data from those domains.

And then it uses all that info to “display customized advertisements about products and services that may be of interest to you,” among other things. It reserves the right to “collect, analyze, and share information” in order to provide you with “advertising and direct marketing communications about products and services offered by Samsung and third parties that are tailored to your interests.”

Speaking of ads, there’s a whole other can of worms about that.

But wait: Isn’t all of this already happening with Google, anyway? That’s a valid question. And the answer is: not really. First, and most crucially, Google never sells your data or shares it with any third parties, even when said info is used to help determine what ads you see around the web via Google’s ad networks. That’s where the Samsung thing gets especially icky-feeling and potentially concerning, if you ask me — in the selling of information to other companies.

But beyond that, Google’s use of data for ad personalization is a well-known, core part of its business at this point. Love it or hate it, Google’s incredibly up-front about what type of data it’s collecting and how exactly it’s using it. The company’s got entire websites devoted to that subject, with plain-English, non-legalese breakdowns. And it makes it possible to see exactly what information is being stored about you and to opt out of any form of data-driven activity you want — including the entire ad personalization system — with the understanding, of course, that doing so will affect what features are available to you in certain associated areas.

Samsung’s use of customer data, in contrast, feels slightly sneaky. Sure, you might’ve clicked through some sprawling terms of service screen when you first set up your phone — who can remember? — but the company certainly isn’t going out of its way to make sure you understand and can control exactly what it’s doing with your data. And the fact that its Android-integrated apps effectively give it access to your data from the underlying Google services — like your calendar details, for instance — make it tough not to see those apps in a completely different light, given the realization of what Samsung reserves the right to do with that data.

I reached out to Samsung on Monday to see if the company could provide any further context or comment about any of this. I’ll update this page if I receive any additional information.

Ultimately, though, it boils down to this: With Android or any Google services, you’re accepting the arrangement with Google and entrusting Google to keep your data safe. That’s the company’s entire business, and presumably, you believe it can do a reasonably decent job of protecting your personal and/or work-connected information, even if it does use parts of that info for ad personalization.

When you add Samsung’s software into the equation, you’re creating a secondary layer that sits on top of that — and consequently doubles the number of companies with access to your info and the responsibility to guard it. (Also, one of those companies is openly claiming the right to pass some of your data on further as it sees fit, in addition to using it for its own secondary system of ad serving.) You’re doubling your exposure, in other words, or more than doubling it once you factor in the third-party sharing.

When we talk about Android and privacy — just like when we talk about Android and software support or Android and overall user experience — it’s worth remembering that two very different realities exist: the one Google creates and provides via its own Android phones and the one other companies adapt to their own priorities and business interests. If you opt to venture outside of Google’s jurisdiction and into another galaxy, it’s critical to keep that distinction in mind and take it upon yourself to seek out and disable any secondary layers that you don’t want in your mobile-tech equation.