Gut reaction

- OUTLINE

- 07 November 2018

Existing treatments bring only temporary relief to people with ulcerative colitis, a common form of inflammatory bowel disease. Insights into the immunobiology of the condition are driving the development of therapies that could lead to prolonged periods of remission.

- Michael Eisenstein 1. Michael Eisenstein is a science writer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

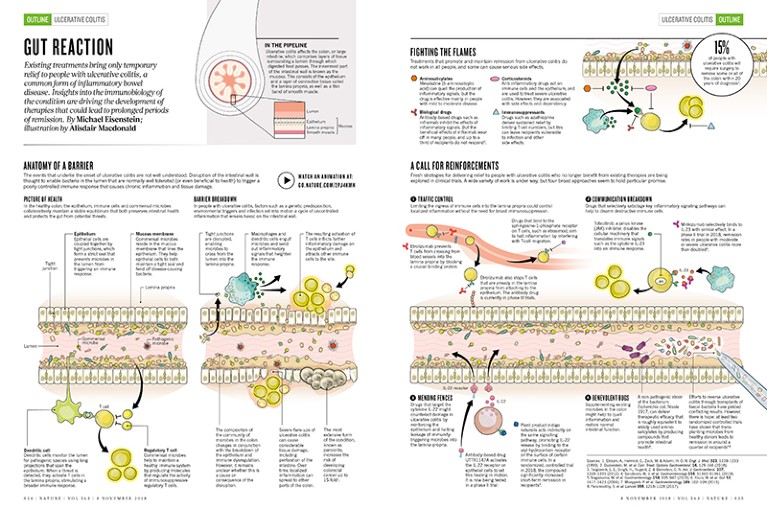

In the pipeline

Ulcerative colitis affects the colon, or large intestine, which comprises layers of tissue surrounding a lumen through which digested food passes. The innermost part of the intestinal wall is known as the mucosa. This consists of the epithelium and a layer of connective tissue called the lamina propria, as well as a thin band of smooth muscle.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

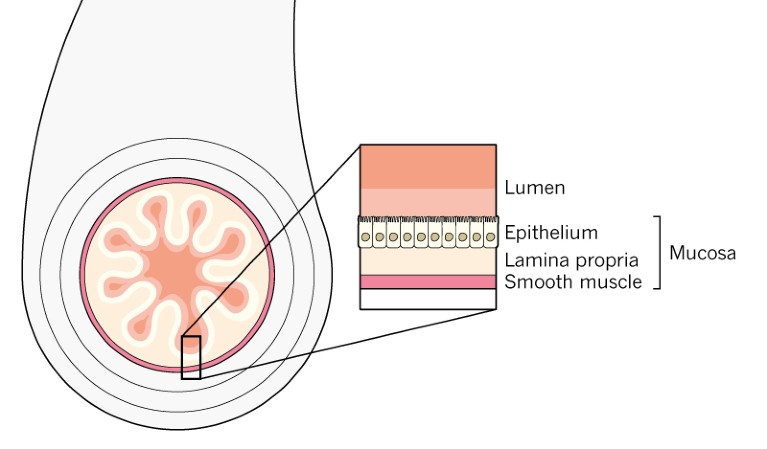

Anatomy of a barrier

The events that underlie the onset of ulcerative colitis are not well understood. Disruption of the intestinal wall is thought to enable bacteria in the lumen that are normally well tolerated (or even beneficial to health) to trigger a poorly controlled immune response that causes chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

Picture of health

In the healthy colon, the epithelium, immune cells and commensal microbes collaboratively maintain a stable equilibrium that both preserves intestinal health and protects the gut from potential threats.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

Epithelium Epithelial cells are coupled together by tight junctions, which form a strict seal that prevents microbes in the lumen from triggering an immune response.

Mucous membrane Commensal microbes reside in the mucous membrane that lines the epithelium. They help epithelial cells to both maintain a tight seal and fend off disease-causing bacteria.

Dendritic cell Dendritic cells monitor the lumen for pathogenic species using long projections that span the epithelium. When a threat is detected, they activate T cells in the lamina propria, stimulating a broader immune response.

Regulatory T cell Commensal microbes help to maintain a healthy immune system by producing molecules that regulate the activity of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells.

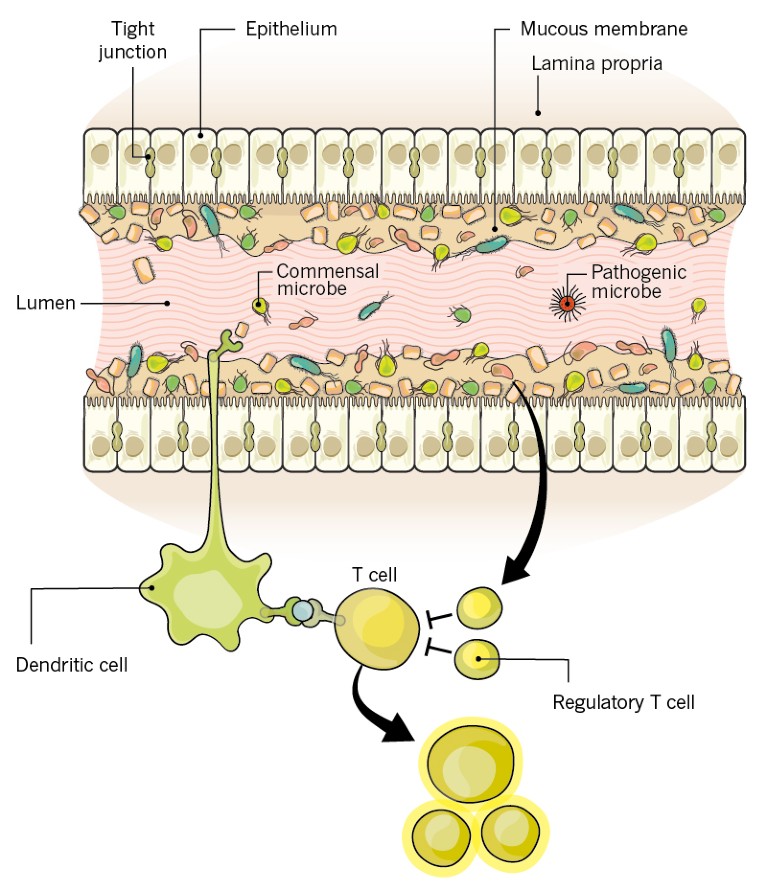

Barrier breakdown

In people with ulcerative colitis, factors such as a genetic predisposition, environmental triggers and infection set into motion a cycle of uncontrolled inflammation that wreaks havoc on the intestinal wall.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

1. Tight junctions are disrupted, enabling microbes to cross from the lumen into the lamina propria.

2. Macrophages and dendritic cells engulf microbes and send out inflammatory signals that heighten the immune response.

3. The resulting activation of T cells inflicts further inflammatory damage on the epithelium and attracts other immune cells to the site.

4. The composition ofthe community of microbes in the colon changes in conjunction with the breakdown of the epithelium and immune dysregulation. However, it remains unclear whether this is a cause or consequence of the disruption.

5. Severe flare-ups of ulcerative colitis can cause considerable tissue damage, including perforation of the intestine. Over time, localized inflammation can spread to other parts of the colon.

6. The most extensive form of the condition, known as pancolitis, increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer up to 15-fold1.

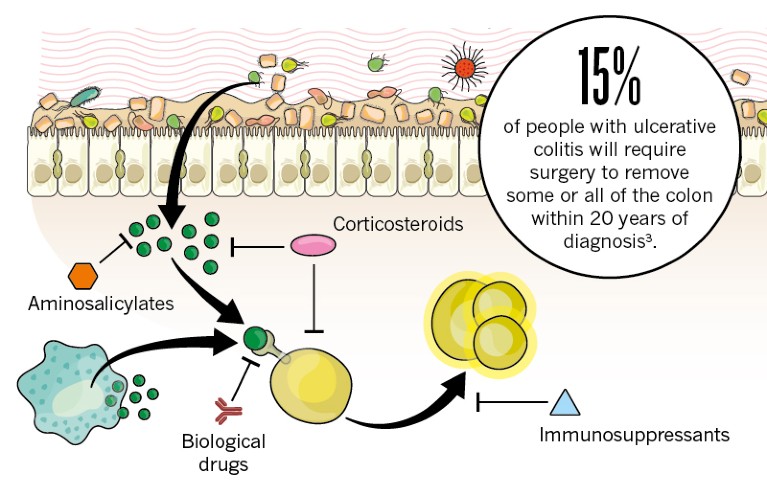

Fighting the flames

Treatments that promote and maintain remission from ulcerative colitis do not work in all people, and some can cause serious side effects.

Aminosalicylates Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) can quell the production of inflammatory signals, but the drug is effective mainly in people with mild to moderate disease.

Corticosteroids Anti-inflammatory drugs act on immune cells and the epithelium, and are used to treat severe ulcerative colitis. However, they are associated with side effects and dependency.

Biological drugs Antibody-based drugs such as infliximab inhibit the effects of inflammatory signals. But the beneficial effects of infliximab wear off in many people, and up to a third of recipients do not respond2.

Immunosuppressants Drugs such as azathioprine deliver sustained relief by limiting T-cell numbers, but this can leave recipients vulnerable to infection and other side effects.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

A call for reinforcements

Fresh strategies for delivering relief to people with ulcerative colitis who no longer benefit from existing therapies are being explored in clinical trials. A wide variety of work is under way, but four broad approaches seem to hold particular promise.

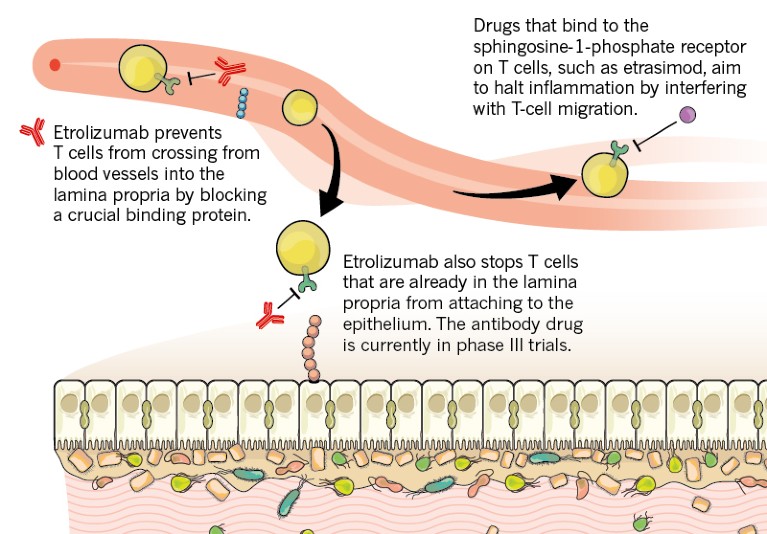

1. Traffic control Limiting the ingress of immune cells into the lamina propria could control localized inflammation without the need for broad immunosuppression.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

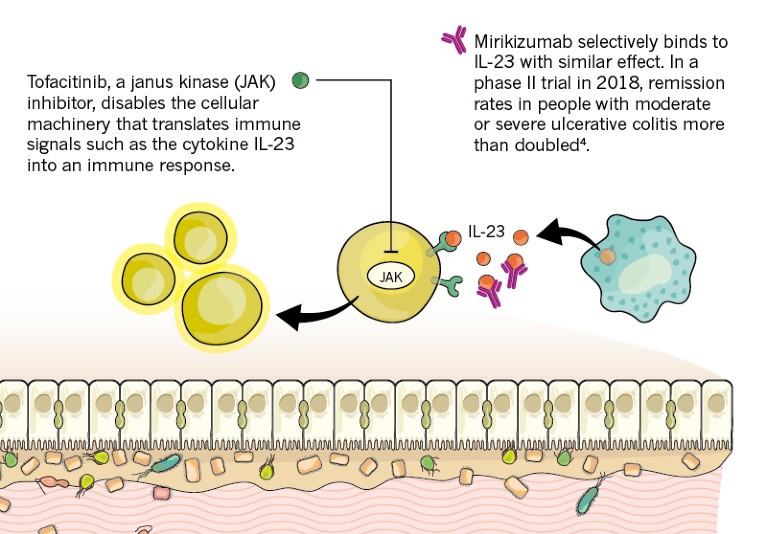

2. Communication breakdown Drugs that selectively sabotage key inflammatory signaling pathways can help to disarm destructive immune cells.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

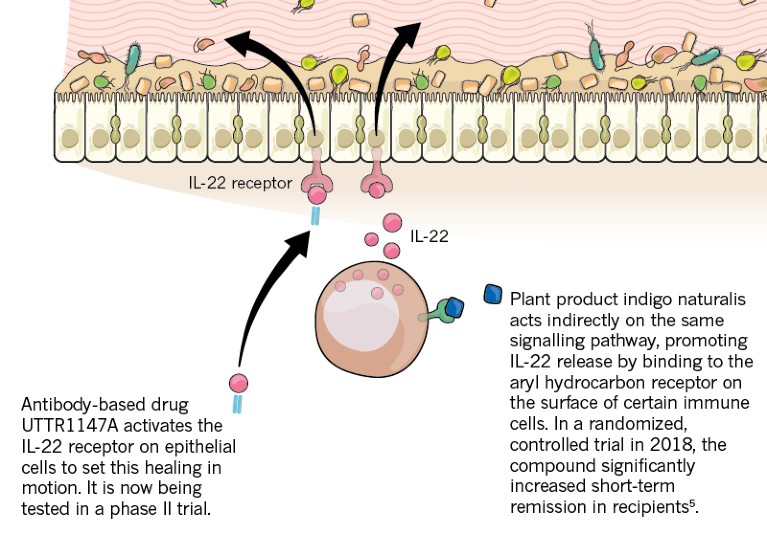

3. Mending fences Drugs that target the cytokine IL-22 might counteract damage in ulcerative colitis by reinforcing the epithelium and halting leakage of immunity- triggering microbes into the lamina propria.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

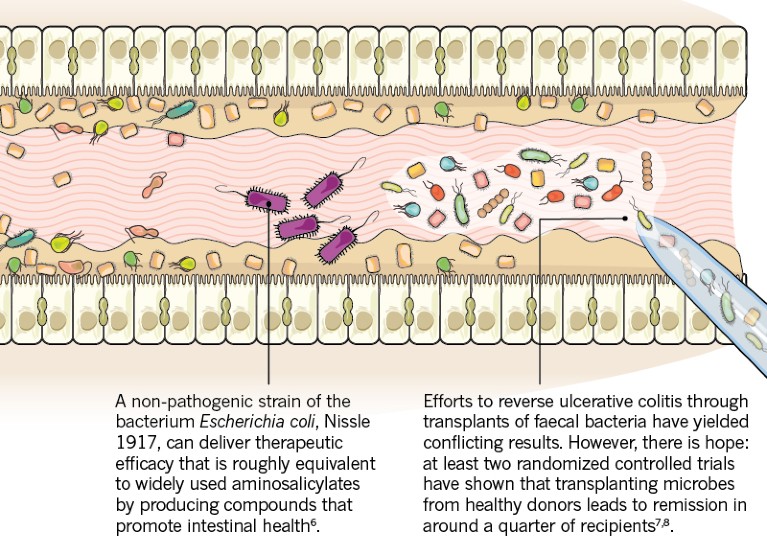

4. Benevolent bugs Supplementing existing microbes in the colon might help to quell inflammation and restore normal intestinal function.

Credit: Alisdair Macdonald

This article is part of Nature Outline: Ulcerative colitis, an editorially independent supplement produced with the financial support of third parties. About this content.

References

- Ekbom, A., Helmick, C., Zack, M. & Adami, H. O. N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 1228–1233 (1990).

- Duijvestein, M. et al. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 16, 129–146 (2018).

- Targownik, L. E., Singh, H., Nugent, Z. & Bernstein, C. N. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 107, 1228–1235 (2012).

- Sandborn, W. J. et al. Gastroenterology 154, S1360–S1361 (2018).

- Naganuma, M. et al. Gastroenterology 154, 935–947 (2018).

- Kruis, W. et al. Gut 53, 1617–1623 (2004).

- Moayyedi, P. et al. Gastroenterology 149, 102–109 (2015).

- Paramsothy, S. et al. Lancet 389, 1218–1228 (2017).